- Home

- Directory

- Shop

- Underwater Cameras - Photographic Accessories

- Smartphone Housings

- Sea Scooters

- Hookah Dive Systems

- Underwater Metal Detectors

- Dive Gear

- Dive Accessories

- Diving DVD & Blu-Ray Discs

- Diving Books

- Underwater Drones

- Drones

- Subscriptions - Magazines

- Protective Cases

- Corrective Lenses

- Dive Wear

- Underwater Membership

- Assistive Technology - NDIS

- On Sale

- Underwater Gift Cards

- Underwater Art

- Power Stations

- Underwater Bargain Bin

- Brands

- 10bar

- AOI

- AquaTech

- AxisGo

- Backscatter Underwater Video and Photo

- BLU3

- Cayago

- Chasing

- Cinebags

- Digipower

- DJI

- Dyron

- Edge Smart Drive

- Eneloop

- Energizer

- Exotech Innovations

- Fantasea

- Fotocore

- Garmin

- Geneinno

- GoPro

- Hagul

- Hydro Sapiens

- Hydrotac

- Ikelite

- Indigo Industries

- Inon

- Insta360

- Intova

- Isotta Housings

- Jobe

- JOBY

- Kraken Sports

- LEFEET

- Mirage Dive

- Nautica Seascooters

- Nautilus Lifeline

- NautiSmart

- Nitecore

- Nokta Makro

- Oceanic

- Olympus

- OM System

- Orca Torch

- Paralenz

- PowerDive

- QYSEA

- Scubajet

- Scubalamp

- Sea & Sea

- SeaDoo Seascooter

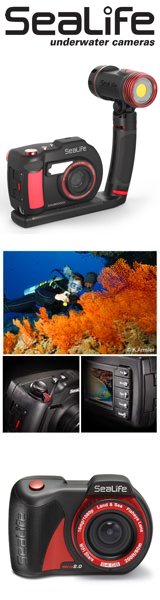

- SeaLife

- Seavu

- Shark Shield

- Sherwood Scuba

- Spare Air

- StickTite

- Sublue

- Suunto

- SwellPro

- T-HOUSING

- Tusa

- U.N Photographics

- Venture Heat

- XTAR

- Yamaha Seascooter

- Youcan Robot

Stars in the Sea

Contributed by Tim Hochgrebe

Driven

by a love of the sea and its largest fish, the elusive whale shark, Australian

naturalist Brad Norman has received a Rolex Award for Enterprise for creating

a worldwide photo-identification system which enables ordinary people to assist

in its conservation.

Driven

by a love of the sea and its largest fish, the elusive whale shark, Australian

naturalist Brad Norman has received a Rolex Award for Enterprise for creating

a worldwide photo-identification system which enables ordinary people to assist

in its conservation.

Before the swimmer's eyes, glowing flecks shine like stars eerily transposed into the depths of the sea. Through a blue-dark veil of water, a huge shape gradually resolves itself, rising slowly and majestically to the surface.

After hundreds of sightings, Brad Norman's blood still thrills as the great, spotted whale shark comes into view, gliding effortlessly forward, its pale, metre-wide mouth agape to scoop up thousands of litres of protein-rich sea water. "When they are down deep, they resemble a starfield under water," he says "As you swim above, the shark's body seems to disappear and its white spots light up like stars in the night sky. It's an awe-inspiring sight."

The imagery illumines the abiding passion of this 38-year-old Australian naturalist who has dedicated most of his adult life to the pursuit, identification, understanding and protection of the world's largest fish, Rhincodon typus, the aptly named whale shark. Reaching 18 metres in length, the huge beast resembles nothing so much as "a bus under water", Norman says. Yet an animate, placid, occasionally inquisitive bus, pursuing its mysterious life across tens of thousands of kilometres of open ocean.

First recorded in 1828, only 350 whale-shark sightings were recorded in the ensuing 150 years. Recent growth in underwater tourism has brought a surge in sightings. Yet the whale shark remains elusive, and the World Conservation Union (IUCN), which engaged Norman to assess the species, regards it as "vulnerable" to extinction. It is protected in only a handful of countries.

The whale shark is one of only three sharks that are filter-feeders, using gill rakers to scoop up krill (shrimp), small fish and other tiny ocean life as its sole source of sustenance. It has never been known to attack humans. Tagged individuals have been tracked for 13,000 kilometres across the Pacific, and 3,000 kilometres in the Indian Ocean. It has an uncanny instinct for locating food concentrations. It is sighted at more than 100 places around the globe - including the Philippines, South China Sea and Indonesia, off India, Australia and Africa, off Mexico, the United States and the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador). Yet it remains so scarce almost nothing is known of its abundance, breeding habits or habitat preferences.

It has few natural enemies, though orcas and predatory sharks may attack young whale sharks. Now, however, the whale shark has joined the long list of species to suffer the insatiable human appetite for seafood. Its flesh, fins and body parts are appearing in growing quantities in Asian markets where they fetch $US18 a kilo or more.

Brad

Norman is determined to find out far more about these fish. His visionary plan

to involve thousands of ordinary people worldwide in the photo-monitoring and

conservation of whale sharks, significantly enhancing knowledge of this elusive

species, has earned him a 2006 Rolex Award for Enterprise - the first Australian

to do so in 25 years.

Brad

Norman is determined to find out far more about these fish. His visionary plan

to involve thousands of ordinary people worldwide in the photo-monitoring and

conservation of whale sharks, significantly enhancing knowledge of this elusive

species, has earned him a 2006 Rolex Award for Enterprise - the first Australian

to do so in 25 years.

Since his first awed encounter in 1994, in Western Australia's Ningaloo Marine Park, Norman has striven to uncover all he can about this lordly animal, whose ancestry extends back 500 million years. "My first encounter seemed quite surreal. There was this huge, living thing coming directly towards me. My eyes were popping out of my head. I almost 'swallowed my snorkel'. I was screaming silently to myself in excitement," he recalls. "Yet, oddly, I wasn't afraid. I just floated there, too amazed to swim after him."

As his encounters multiplied, Norman grew to appreciate many aspects of the whale shark. Its economical 1-to-1.5 metres per second cruising speed was perfect for observation. Though able to dive as deep as 1,500 metres, it often swam conveniently near the surface. Its placid temperament made it safe compared with other big sharks. Yet it could also be dynamic: "I once observed seven in an area where there was a huge swarm of krill, a real soup of food in the water. They were charging through it, mouths open, thrashing around. That was a big adrenalin rush. I never felt frightened, but I did keep my arms down and made myself small.

"Even with something as big as a whale shark, you're not afraid - and nor is it. It is a calming experience. You feel at one." Swimming alongside its head, Norman has seen its little eye turn, observing him - a glimmer of acknowledgement. "Maybe it just thinks I'm a big remora [sucker fish]," he laughs. Nonetheless, he respects the shark's brute power, and has assisted in the drafting of guidelines for divers and tour operators worldwide on how to behave around whale sharks.

Norman's

love of the ocean was born on the golden beaches of Perth, on Australia's Indian

Ocean coastline, where he body-surfed as a youngster. This led to diving and,

via a science degree, to a deep interest in marine conservation which he has

pursued as a researcher and fisheries management consultant.

Norman's

love of the ocean was born on the golden beaches of Perth, on Australia's Indian

Ocean coastline, where he body-surfed as a youngster. This led to diving and,

via a science degree, to a deep interest in marine conservation which he has

pursued as a researcher and fisheries management consultant.

His encounter with the whale sharks of Ningaloo was a life-altering experience. The shark was an unknown, and there was little money for its study or conservation. Norman survived hand-to-mouth on sporadic grants, and funded much research himself. Burning the midnight oil, he mounted national and international campaigns for the whale shark's conservation, emerging as a global expert on the animal and its needs. He helped authorities develop plans for its protection, wrote scientific reports and information for divers and children.

Many mysteries of the whale shark remain to be solved. While young males gather at Ningaloo, no one knows where the females collect or where the sharks breed. The key to studying their thin, dispersed and cryptic demographics lay in identifying individuals. Following a clue provided by an experienced fisherman, Norman's painstaking research managed to prove that every whale shark has a pattern of white spots on its body as individually distinctive as a human fingerprint. This gave him the idea of using underwater camera images as a practical, non-invasive way to identify individuals. In 1999 he set up the ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-identification Library on the Internet, a global project to record sightings and images.

Despite the growing body of information, Norman lacked an efficient way to compare shots of whale sharks taken from different angles, under varying conditions and fish postures. In 2002, a US computer engineer and fellow diver Jason Holmberg contacted him, offering to help organize and automate the ECOCEAN database. He explained the photo-ID problem to a friend, NASA-affiliated astronomer Zaven Arzoumanian, whose colleague Gijs Nelemans pointed out that a technique used by Hubble Space Telescope scientists for mapping star patterns known as the Groth algorithm, might also be useful for recognising whale sharks by mapping the unique patterns of white spots on the shark's hide. It took many months of calculations and computer programming to refine the algorithm for use on a living creature - but in the end they gained a breakthrough for biology: a reliable way to identify individuals in virtually any spotted animal population, without tagging or harassing them. In 2005, the three reported their findings in the Journal of Applied Ecology. More than 500 whale sharks have since been identified and added to the database using the technique.

For survival, whale sharks depend on huge bursts of tiny sea life which, in turn, reflect the condition of the oceans and their bio-productivity. Since whale sharks travel immense distances to collect food, the demographics of these fish can serve as an indicator of ocean health - and of the human impact on it.

This

is high, planet-scale science. But at another scale individual divers worldwide

can now follow Norman's simple guidelines for photographing whale sharks and

log their images, activities and locations on the ECOCEAN site. Ordinary people

can take part in real science. On ECOCEAN, their photos are automatically catalogued,

compared and, if possible, identified as belonging to a known individual. Each

new image helps Norman compile a global map of where whale sharks live and their

migratory patterns. Contributors receive notice by email of all past and further

sightings of 'their' shark. Together, the images are helping to build a global

picture of the abundance, health, range and fluctuations of the whale shark

population. "Just about anyone with a disposable underwater camera can now play

a part in helping to conserve whale sharks, and so help to monitor the health

of the oceans," Norman explains. "It gives people a direct stake in whale shark

stewardship."

This

is high, planet-scale science. But at another scale individual divers worldwide

can now follow Norman's simple guidelines for photographing whale sharks and

log their images, activities and locations on the ECOCEAN site. Ordinary people

can take part in real science. On ECOCEAN, their photos are automatically catalogued,

compared and, if possible, identified as belonging to a known individual. Each

new image helps Norman compile a global map of where whale sharks live and their

migratory patterns. Contributors receive notice by email of all past and further

sightings of 'their' shark. Together, the images are helping to build a global

picture of the abundance, health, range and fluctuations of the whale shark

population. "Just about anyone with a disposable underwater camera can now play

a part in helping to conserve whale sharks, and so help to monitor the health

of the oceans," Norman explains. "It gives people a direct stake in whale shark

stewardship."

With the Rolex Award money, Brad Norman is devoting two years full-time to his project, training local authorities, tourism operators and 20 research assistants around the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans to observe, record and protect whale sharks. In this way he will develop whale shark photography as a significant tool for conservation.

He plans also to explain to those who hunt the shark that there is more to be gained by leaving it alive. Ningaloo's whale sharks draw more than 5,000 visitors a year, mainly from April to June, generating ecotourism worth an estimated US$10 million, proving a live whale shark earns far more than a dead one.

"The whale shark is worth saving - and we can do something about it," Brad

says. "It is a big, beautiful and charismatic animal, and not dangerous. It

is a perfect flagship for the health of the oceans."

Dennis Beros, of the Australian Marine Conservation Society, observes: "Brad

Norman has always struck me with his complete dedication to whale shark research.

His approach is invariably tenacious and I have no doubt he will leave an indelible

mark on the conservation of this species."

Shopfront

-

Submersible Systems Spare Air Pack - Model 300 - 3cuf

Submersible Systems Spare Air Pack - Model 300 - 3cuf

- Price A$ 549.00

-

SwellPro - FishingDrone 1 LiPo battery

SwellPro - FishingDrone 1 LiPo battery

- Price A$ 249.00

-

Scubalamp D-Pro Underwater Strobe

Scubalamp D-Pro Underwater Strobe

- Price A$ 1,199.00

-

Sublue Navbow+ Underwater Scooter

Sublue Navbow+ Underwater Scooter

- Price A$ 2,399.00

-

Scubalamp PV32T LED Photo/Video Light - 3,000 lumens

Scubalamp PV32T LED Photo/Video Light - 3,000 lumens

- Price A$ 349.00

-

CineBags - CB71 Jumbo Dome Port Case

CineBags - CB71 Jumbo Dome Port Case

- Price A$ 143.95

-

SeaLife Sea Dragon 3000SF Pro Dual Beam Photo-Video light

SeaLife Sea Dragon 3000SF Pro Dual Beam Photo-Video light

- Price A$ 949.00

-

SeaLife Protective Gear Pouch

SeaLife Protective Gear Pouch

- Price A$ 34.95

In the Directory